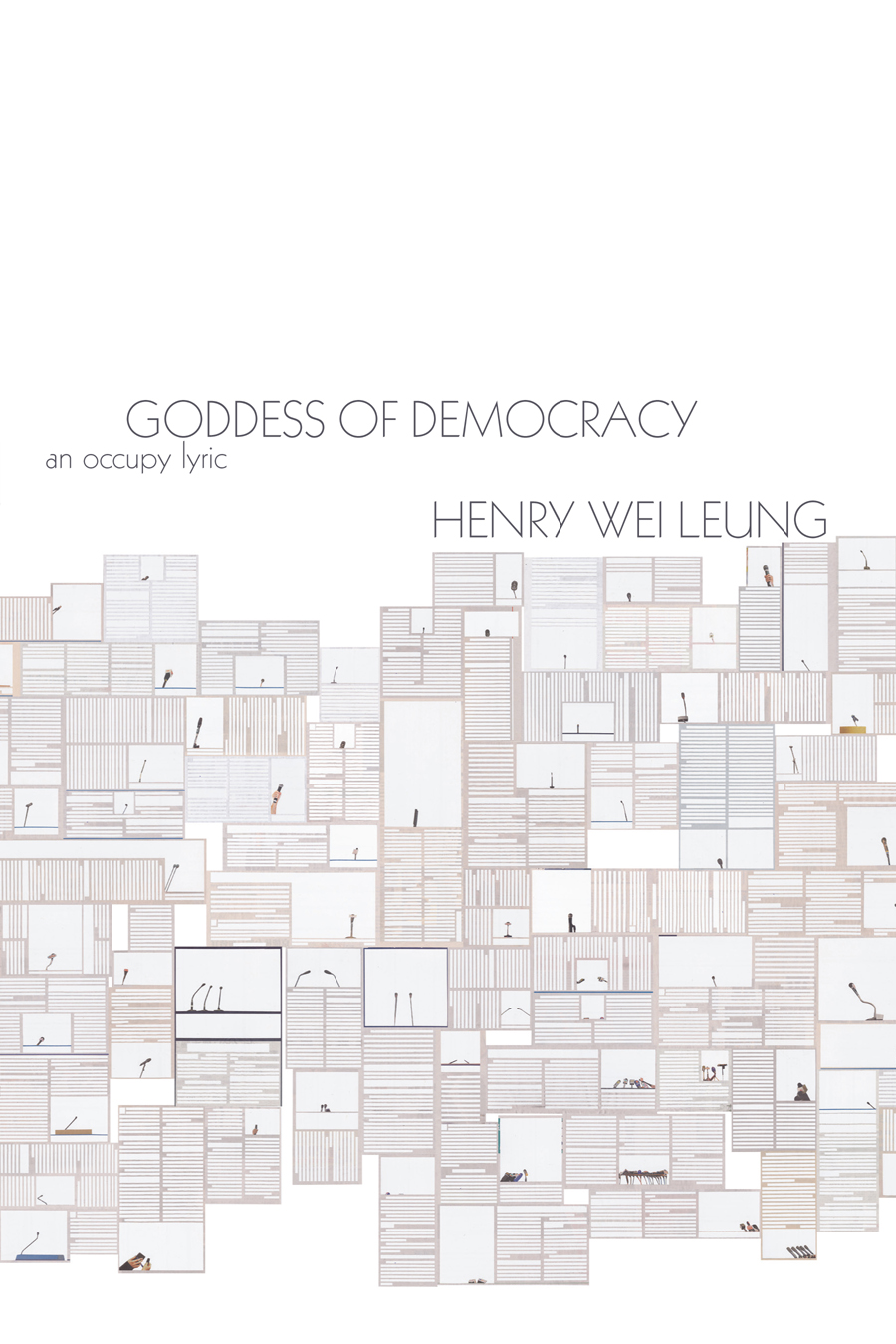

A Review of Henry Wei Leung’s Goddess of Democracy: An Occupy Lyric (Omnidawn Publishing, 2017)

By Gnei Soraya Zarook

I want to preface this review by admitting that I have only engaged with two texts that count as ‘poetry’ before encountering Henry Wei Leung’s Goddess of Democracy: An Occupy Lyric: Shailja Patel’s Migritude and Claudia Rankine’s Citizen. Thanks to a seminar two quarters ago on Law and Literature, I am now able to add two more works to that list: Craig Santos Perez’s from Unincorporated Territory and Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas. Of every other bit of poetry I was assigned in American Literature survey courses through my undergraduate career, I unfortunately have no recollection.

My preface here is meant to do two things: (1) ask forgiveness in the mistakes you are likely to find as a result of my ignorance of the formal characteristics of poetry, which is limited to knowing what a stanza is, and (2) bring attention to the fact that the only works of poetry I have read have all been works that are not just poetry in the traditional layperson sense of the word; they are all poetry with an asterisk, prose poetry, poetry/prose, poetry/essay, and so on. But more than that, they all seem to embody an ethics of protest, and thus they all make me feel things about the people and events that they are about.

Goddess of Democracy: An Occupy Lyric is no different, and so this review will focus mostly on how I have felt reading it, because that is the most that I can offer to this extraordinary text. I will let Omnidawn provide a more eloquent summary of what this work is than I am capable of: “Written in and of the protest encampments of one of the most sophisticated Occupy movements in recent history, Goddess of Democracy attempts to understand the disobedience and desperation implicated in a love for freedom. Part lyric, part autoethnography, part historical document, these poems orbit around the manifold erasures of the Umbrella protests in Hong Kong in 2014. Leung, who was in those protests while on a Fulbright grant, navigates the ethics of diasporic dis-identity, of outsiderness and passing, of privilege and the pretension of understanding, in these poems which ask: “what is / freedom when divorced from / from?”

Never quite knowing what to do with poetry on its own, I was hesitant at the first poem, “Preamble: Room for Cadavers,” but I was immediately arrested by the images and the focus on the body, and by the sense of love and care in phrases like the following:

I never thought we came apart like this,

like sheet, like blanket, pillow after pillow

unpeeled by morning, trace of warmth

where once a body swelled. (17)

The first section of the book, titled “Neither Donkey Nor Horse,” meditates on the Goddess of Democracy, the 33-foot paper mache statue built by university students during the 1989 Democracy Movement in Tiananmen Square. The status was destroyed by soldiers during the Tiananmen Massacre in June 1989. As I learned of this history, what is at stake in a work like this became clear, for I had previous knowledge of the Tiananmen Massacre, but none whatsoever of the Goddess of Democracy. And so it becomes fitting the many absences in the poem, the many spaces and redacted phrases, the words thrown across the page in what seems, at first, to be a random scatter. Thus I felt deeply implicated reading the following lines from “Disobedience,” which allowed me to pause and assess my intrusion into a text that asks questions of the failures of democracy and of memory:

I was not meant to survive.

So forgive my participation.

Forgive me my love for freedom

and for my foreign question: what is

freedom when divorced from

from? (20)

The poem’s narrator is a foreigner in the sense that they have lived overseas and have now returned to their country of origin and is part of a protest. Cathy Park Hong writes in the introduction to the book about these last three lines: “Leung doesn’t give us an accessible individualized account to pull at the American reader’s heartstrings but instead uses his first-hand insights to interrogate Western ideologies of democracy: ‘what is freedom when divorced from from?’ I agree; the book consistently remind the reader that it is written for a specific audience, and that the reader may not be that audience. This kind of refusal reminds me of Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric, a similar collection of prose poetry that archives the experiences of black women and people of color as they experience daily microaggressions. If you know or experience the instances that comprise the text, you resonate with it differently. Leung is speaking to someone in particular, and everyone else can listen in on this conversation.

Another of my favorite pieces was the one titled “BRIDGE IN” on page 29, which I was thrilled to find is a companion piece to “(Abridged Timeline: Hong Kong 2014)” on page 93. The title of the first piece comes from letters and words taken out of the second piece. The first piece is mostly blank, and is missing several events, so that it provides only a shattered, incomplete picture that is hardly a picture at all. Only once the reader has paid attention by reading through to the end are they allowed the complete timeline. And yet, the entire process is one of recognizing that when it comes to things such as timelines, there are no such things as clean ‘start’ and ‘end’ dates, and no such thing as ‘complete.’

As June, 4, 2019 approaches, marking thirty years since the Tiananmen Square Massacre, Leung’s work asks us to meditate on how complicated it is to remember violence, protest, sacrifice, and symbols of resistance, even ones that were taken down. In refusing a full picture and asking to what extent we can ethically recreate the loss, trauma, and victory of protest, one of the things Goddess of Democracy does so well is revel in the knowledge of precisely how much work the placement, absence, and presence of words can demand of us to respond, to question, to remember, and to occupy, long after a tangible protest seems 'over.'

Buy the Book Here!

Gnei Soraya Zarook, PhD Student in English, at gzaro001@ucr.edu