Written by Stephen Hong Sohn

Edited by Corinna Cape

*reviewer’s note: In my aim to cover as much ground and texts as I can, I’m focusing on shorter lightning reviews that get to the gist of my reading experience! As Asian American literature has boomed, my time to read this exponentially growing archive has only diminished. I will do my best, as always!

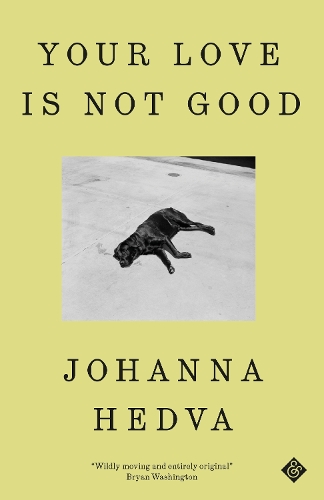

Well, if there was any novel that is the narrative embodiment of Lady Gaga’s “Bad Romance,” then it is Johanna Hedva’s Your Love is Not Good (And Other Stories, 2023). Let’s let the description at the official publisher’s website give us some much-needed grounding: “At an otherwise forgettable party in Los Angeles, a queer Korean American painter spots a woman who instantly controls the room: gorgeous and distant and utterly white, the centre of everyone’s attention. Haunted into adulthood by her Korean father’s abandonment of his family, as well as the spectre of her beguiling, abusive white mother, the painter finds herself caught in a perfect trap. She wants Hanne, or wants to be her, or to sully her, or destroy her, or consume her, or some confusion of all the above. Since she’s an artist, she will use art to get closer to Hanne, beginning a series of paintings with her new muse as model. As for Hanne, what does she want? Her whiteness seems sometimes as cruel as a new sheet of paper. When the paintings of Hanne become a hit, resulting in the artist’s first sold-out show, she resolves to bring her new muse with her to Berlin, to continue their work, and her seduction. But, just when the painter is on the verge of her long sought-after breakthrough, a petition started by a Black performance artist begins making the rounds in the art community, calling for the boycott of major museums and art galleries for their imperialist and racist practices. Torn between her desire to support the petition, to be a success, and to possess Hanne, the painter and her reality become more unstable and disorienting, unwilling to cut loose any one of her warring ambitions, yet unable to accommodate them all. Is it any wonder so many artists self-destruct so spectacularly? Is it perhaps just a bit exciting to think she could too?”

This description is quite robust and actually brings readers up to speed in relation to 2/3 of the novel’s plot. What this summary doesn’t fully convey is the intriguing formal dynamics of the novel, which involve vignette-esque chapters that always begin with an art-based heading. The heading typically references some sort of painting technique or style (e.g. chiaroscuro, tenebrism, impasto, etc), which reminds us that we’re in the specific and rarefied world of artistic production. Perhaps the element that I was most impressed with was Hedva’s incredibly immersive first-person narrator. Hedva’s protagonist is one willing to admit her faults, her obsessions, and many of her most intimate habits. In this respect, we get quite the complicated and textured psychological view of a character who is slowly unraveling. There is a point in the text when the narrator receives a significant head injury, which occurs in a period of time when her artistic future may be in jeopardy. After that incident, I wasn’t quite sure what was going on, as the narrative includes some surrealistic moments in which I began to question the reliability of the storyteller. As Hedva seems to be drawing out, this protagonist has a sadomasochistic relationship not only to others but to art, but the question is whether or not this relationship is fully toxic. The title, which at first seems directed toward the narrator’s relationship to Hanne, might actually be reframed as the distorted parenting which she has received, and which is “not good” for the constitution of her identity over time. Another element of this text that was illuminating concerns the multifaceted relationship between gallerists, artists, and museums. I didn’t realize that an artist could be in that kind of debt—the narrator is hundreds of thousands of dollars in the hole from her various art degrees and contracts—and then could walk into a working relationship with a gallerist, knowing that she would be working overtime with the hopes that her work would eventually sell so that she would be able to cover some of what was owed. Finally, perhaps, the most philosophical element that Hedva ingeniously threads through is the discourse of race as it pertains to art. Since the narrator and many of her friends occasionally produce art that borders on the abstract, the question then becomes: where is race in this work? Should race be at all understood as a framing mechanism for the minority artist? Such questions continually animate multiple narrative sequences, giving readers much to chew on in relation to authorial ancestry and its impact on the way we read artistic production. A truly distinctive novel with an equally singular narrative perspective.

Buy the Book Here