By Stephen Hong Sohn

It’s been ages since I’ve had a chance to feast on some magisterial short stories. Lucky for us that Viet Thanh Nguyen is a publication machine and has gifted us with The Refugees so soon after Nothing Ever Dies and The Sympathizer. Let’s hope he keeps churning these gold nugget publications out. In any case, B&N doesn’t really do such a good job of giving us some background on the book, so I’ve gone elsewhere. The Grove Atlantic site gives us this pithy description: “With the coruscating gaze of The Sympathizer, in The Refugees Viet Thanh Nguyen gives voice to lives led between two worlds, the adopted homeland and the country of birth. From a young Vietnamese refugee who suffers profound culture shock when he comes to live with two gay men in San Francisco, to a woman whose husband is suffering from dementia and starts to confuse her for a former lover, to a girl living in Ho Chi Minh City whose older half sister comes back from America having seemingly accomplished everything she never will, the stories are a captivating testament to the dreams and hardships of immigration.” I’m not sure I would call The Sympathizer or The Refugees “coruscating,” but I’ll still give the copy writer an A+ for a great adjective.

Nguyen’s got a deft hand with the short story; the compact style suits him. Each entry in the collection has a fable-like quality. The first, “Black-Eyed Woman,”, sets up the stakes of the collection at large, as a daughter and her mother grapple with ghosts of the past. In some sense, Nguyen is beautifully dredging up the past for the aesthetic purposes of representational resurrections. My favorite story hands-down was “The Other Man,” which details a refugee’s arrival in the United States and his acculturation in San Francisco in the years prior to the AIDS epidemic. In “War Years,” a family grapples with the aggressive fundraising of an anti-communist activist in the Vietnamese community. This story was a tough one, focusing on the complicated political allegiances of families in the wake of war. “The Transplant” was one of the quirkier stories in the collection; the protagonist wants to connect with a family member of the individual who has donated him a liver. In this case, and I’m providing a spoiler warning here, the person who he believes is that family member is someone else entirely.

“I’d Love You to Want Me” was the most poignant collection, as a woman (who very much enjoys working at her local library) deals with the caretaking duties of her husband (a professor), who is slowly losing memory (due to Alzheimer’s. “The Americans” details a family who visits their daughter, who is living in Vietnam. The father is a Vietnam War veteran and returns to Vietnam with mixed emotions. I especially found the conclusion to be affecting. “Someone Else Besides You” explores the life of a recently divorced man; his father is a widower, and he has begun dating again. “Fatherland” involves a young woman who returns to Vietnam to visit her biological family, which she was separated from due to circumstances of the war. Her younger sister realizes that her life in the United States is a fantasy. Nguyen is always at his past looking at the complicated and dysfunctional relationships that bloom among family members. The intricacies of these links flesh out the multifaceted lives of the many refugees that populate these stories.

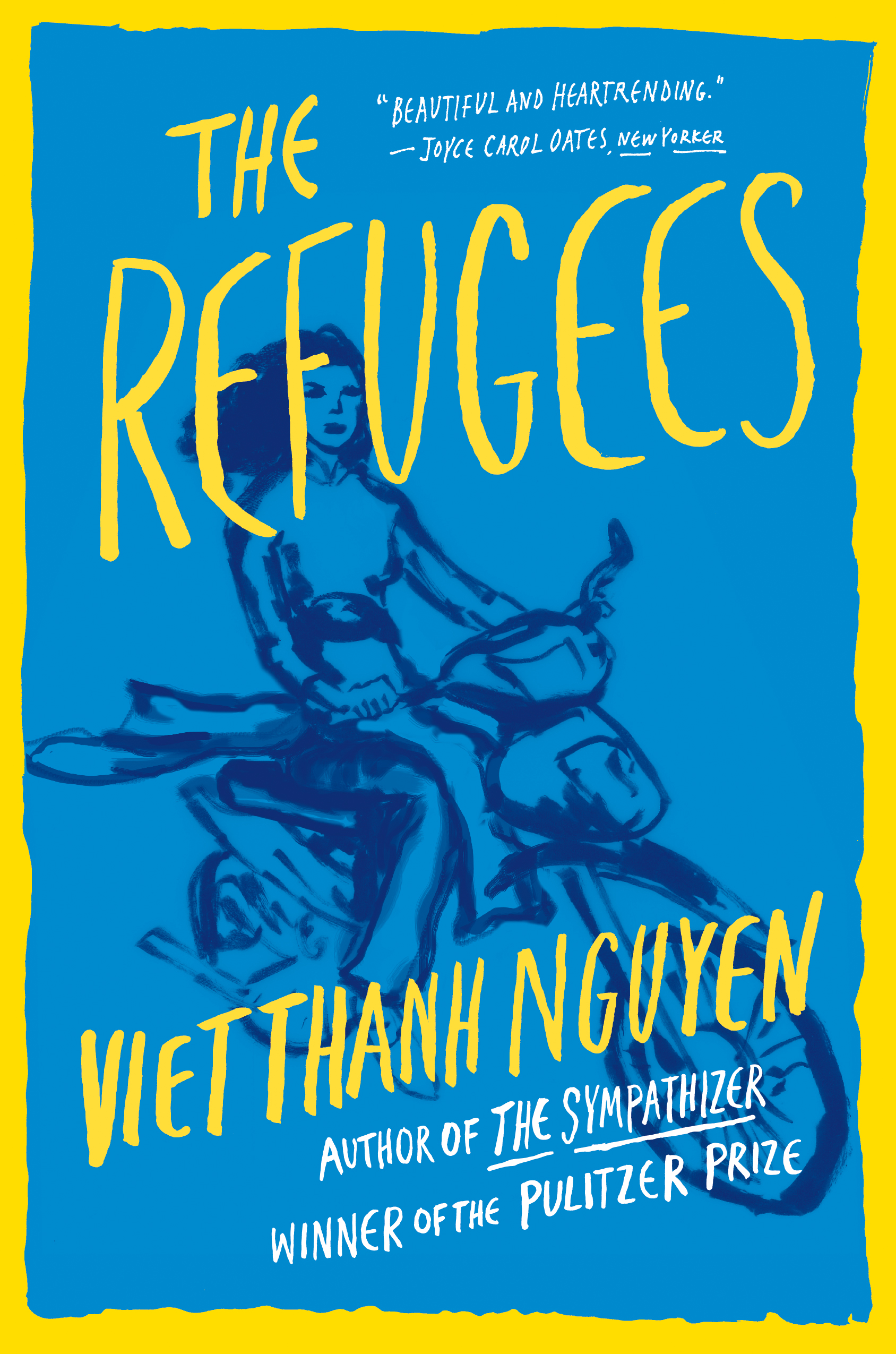

Buy the Book Here:

Review Author: Stephen Hong Sohn

Review Editor: Leslie J. Fernandez

If you have any questions or want us to consider your book for review, please don’t hesitate to contact us via email!

Prof. Stephen Hong Sohn at ssohnucr@gmail.com

Leslie J. Fernandez, PhD Student in English, at lfern010@ucr.edu