Asian American Literature Fans – Megareview for September 21, 2014

With apologies as always for any typographical, grammatical, or factual errors. My intent in these reviews is to illuminate the wide ranging and expansive terrain of Asian Anglophone literatures. Please e-mail ssohnucr@gmail.com with any concerns you may have.

In this post, reviews of: Bilal Tanweer’s The Scatter Here is Too Great (Harper, 2014); Farzana Doctor’s Six Metres of Pavement (Dundurn, 2011); Lily Yuriko Nagai Havey’s Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp (University of Utah Press, 2014); Ed Lin’s Ghost Month (Soho Crime, 2014); Michael Cho’s Shoplifting (Pantheon, 2014).

A Review of Bilal Tanweer’s The Scatter Here is Too Great (Harper, 2014).

Bilal Tanweer’s ambitious and formally inventive debut The Scatter Here is Too Great follows a revolving cast of characters who are linked by one tragic event: a bomb blast in Karachi, Pakistan that leaves many injured and dead. The bomb blast is a red herring, though, and that fact is only made clear in the novel’s final sequence. Indeed, readers might be looking too much into the source of the blast, what caused it, and the motivations for its detonation, without realizing that we’re missing the point. Tanweer’s true protagonist in the city of Karachi, how it has been imagined and remade especially in light of terrorist discourse and the projection of Islamic Fundamentalism on countries in that region. Tanweer’s project, then, is to particularize experience and texturize how the city is interfaced and understood from a variety of different perspectives. Called a “novel in stories,” it follows a number of different characters, shifting narrative perspectives constantly (especially between first and second person). Each section of the novel seems to slightly advance the story, moving us closer and closer physically to the blast. One of the most important connections it seems is the place of the writer in this modernizing city. Indeed, one of the returning figures is a subeditor who is tasked with understanding how to interface with the many facets of Karachi and demystifying its representations. This character muses: “All these stories, I realized, were lost. Nobody was going to know that part of the city as anything but a place where a bomb went off. The bomb was going to become the story of this city. That’s how we lose the city—that’s how our knowledge of what the world is and how it functions is taken away from us—when what we know is blasted into rubble and what is created in its place bears no resemblance to what was and we are left strangers in a place we know, that we ought to have known. Suddenly, it struck me that that’s how my father experienced this city. How, when we walked this city, he was tracing paths from his memory to the present—from what this place had been to what it had become” (165). It would seem that the writer in all of his metafictional conceits is taking himself to task for this very same purpose, trying to create some sort of narrative that links time and place to the urban experience. The form of the novel itself is then part of the key to understanding Tanweer’s rhetoric: not everything will cohere, but the fragmentation is part of the complexity and the beauty of Karachi, a city that we understand is more than a bomb, more than Islamic fundamentalism, more than a site that has been determined to be a terrorist stronghold. I agree with other reviewers that the story can sometimes meander in ways that are distracting to readers, but Tanweer’s prose is so compelling, especially the philosophical renderings that appear in the opening and closing chapters that you’ll be lulled into Karachi’s representationally rich character configurations, including an ambulance driver undone by two figures who seem to represent the end of the world and two young lovers who seek to find a place to be alone in a city with too many eyes.

Buy the book here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Scatter-Here-Too-Great/dp/0062304410/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=undefined&sr=8-1&keywords=the+scatter+here+is+too+great

A Review of Farzana Doctor’s Six Metres of Pavement (Dundurn, 2011).

The great thing about the archive of “literatures penned by writers of Asian descent in English” (otherwise known as Asian Anglophone) is that the depth of its reach seems unending. There’s always a new writer that I find that I feel like I should have already heard of but haven’t, which brings me to Farzana Doctor, a queer Asian Canadian writer, who has published two novels. I review Six Metres of Pavement here, which is told in the third person perspective and primarily follows two characters: Ismail Boxwala, a Muslim Indo Canadian who is divorced, something that occurs in the wake of a tragic accident. He had left his infant daughter in his car while at work and Zubeida (nicknamed Zubi) dies from sun exposure. His wife, Rehana, attempts to assuage to the situation by suggesting they have another child, but Ismail suffers erectile dysfunction, no doubt related to his anxiety that he cannot possibly father another child, fearing that he may again be negligent. Celia Sousa has just moved into the neighborhood with his daughter Lydia and her son-in-law. Celia is in mourning; her mother and her husband Jose have both passed away recently, and she struggles to find a way out of her daily melancholy. It’s been about eighteen years since Zubi died when the novel opens, and Ismail struggles with a drinking habit. He falls into meaningless sexual dalliances with women at the local bar; he also strikes up a friendship and sexual relationship with a local there named Daphne, who ends up proclaiming her queerness and then joining an AA group. It is Daphne who encourages Ismail to take a creative writing class, and it is there that Ismail makes a strong friendship with a fellow classmate Fatima, even after he questions whether or not to stay enrolled (Daphne quickly drops out of the class leaving Ismail abandoned). It’s quite clear from the get-go that Doctor is setting up a romance plot between Ismail and Celia, and it takes too long to get there, but fortunately Doctor also provides us with an interesting friendship plot that occurs between Fatima and Ismail. Both Fatima and Ismail hail from similar ethnic backgrounds (though Fatima is a generation younger) and when Fatima is thrown out of the house, with no support for her livelihood, education, and other such things, she has to increasingly rely on Ismail’s help just to survive. Fatima, as we soon discover, is a feminist, an anticolonialist, steeped in academic rhetoric concerning social inequality, and most importantly for our understanding: she’s a lesbian. gasp To a certain extent, Doctor’s structure strangely enough replicates a heteronormative family unit, as at one point, it seems possible that Ismail will marry Celia, and that Fatima has become a kind of surrogate daughter (a kind of imperfect replacement for Zubi). Though the novel takes too long to set up the connection between Celia and Ismail—indeed, Doctor is a talented writer and it’s perfectly clear that both characters are traumatized, so we could have used some editing in the first 100 pages—the sociopolitical import of the novel is obvious, and the novel especially provides the kind of ending not usually fit for so many characters who exist on society’s fringes. Somehow, Doctor manages to provide us with a convincing ending where outcasts and pariahs do not necessarily succumb to violent deaths and premature termination from the plotting.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Six-Metres-Pavement-Farzana-Doctor/dp/1554887674/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1408805340&sr=8-1&keywords=six+metres+of+pavement

A Review of Lily Yuriko Nagai Havey’s Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp (University of Utah Press, 2014).

What an absolutely amazing book! There can be no other estimation for such an important document that is part of the long-standing recovery effort related to the Japanese American internment experience. Lily Yuriko Nagai Havey’s Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp is a mixed-genre, creative nonfiction memoir that employs photographs, narrative, and watercolor paintings to represent and to give life to Havey’s experiences as a ten-year old who first must endure living at an assembly center and then in the harsh conditions of Colorado’s Amache internment camp. The narrative is straightforward enough and one that recalls other internment works (such as Yoshiko Uchida’s Desert Exile, Mitsuye Yamada’s Desert Run, etc) in its depiction of the monotony, the psychic struggles, and the everyday desultory life of languishing in what is basically an inhospitable place. There are moments of pleasure and even happiness, which erupt in Havey’s narrative in unexpected places: the light of the sun when it hits a cold and barren landscape or the return of a father from long periods away (working outside of the internment camp in order to escape its confines and to provide for the family). In other moments, we constantly see how the internees make the most of meager circumstances, continuing to persevere despite their imprisonment. Again, it is the minor moments which surface as a brutal and stark reminder of indomitable spirits, such as the desire of Havey’s mother to continue polishing the pot-bellied stove, or the move to decorate the ramshackle interiors of the interment barracks. But, what makes Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp so dynamic and so indispensable is its visual catalog, one that includes photographs (indeed, as Havey notes, in the last year of the internment camp, a camera was able to be used by residents) and watercolor paintings that Havey created over time to represent her experiences. The watercolor paintings are notable in that they are far from directly representational: most have abstract and symbolic qualities that seem exactly appropriate as a kind of formal conceit that illuminates such a fragmenting and harrowing experience.

Here’s a link to one of the watercolor paintings:

http://artistsofutah.org/15Bytes/index.php/lily-havey-reads-gasa-gasa-girl-goes-to-camp/

Havey often uses pastels (an effect to a certain extent of the watercolor approach), which ends up also functioning within a light scheme that comes off as ghostly. As these watercolors accompany the direct narrative of the internment, a multifaceted portrayal emerges that reminds us of the continued work that needs to be done in order to reconsider how this experience impacted so many Americans (Japanese in ethnicity and otherwise). Finally, I would like to remark on the production quality of this book: the pages used are the kinds found in art and painting studies, with a glossy finish. Certain to stand the test of time, one must pick up this essential and new addition to the canon of internment literatures.

Internment literatures based upon place:

Topaz: Yoshiko Uchida’s Desert Exile; Julie Otsuka’s When the Emperor Was Divine

Minidoka: Mitsuye Yamada’s Camp Notes and Other Writings

Manzanar: Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston’s Farewell to Manzanar

Heart Mountain: Lee Ann Roripaugh’s Beyond Heart Mountain

Poston: Cynthia Kadohata’s Weedflower

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Gasa-Girl-Goes-Camp-Behind/dp/1607813432/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1410191557&sr=8-2&keywords=gasa+gasa+girl

A Review of Ed Lin’s Ghost Month (Soho Crime, 2014).

So when I picked up Ed Lin’s Ghost Month, I automatically assumed it was another book in Lin’s Robert Chow’s detective series (which includes This is a Bust, One Red Bastard, and Snakes Can’t Run). Instead, we have another book entirely, which revolves around Jing-nan (aka Johnny), a twenty-ish character languishing in a life he never wanted (inheriting the debts of his father and running a stall out of Taipei’s famed Night Market) living in a country he doesn’t want (Taiwan). The opening of the novel begins inauspiciously enough with Jing-nan discovering that the love of his life Julia Huang has been murdered. Jing-nan hadn’t kept in touch with Julia because of a promise he made that he would only marry her if he had established himself in a career and with full preparedness for life as a married couple. When he must leave UCLA without finishing his degree and returns to Taiwan, but not soon after, his mother dies in a tragic accident and his father dies just three weeks later due to health issues. Needless to say, Jing-nan’s life is turned upside down. He takes on the family business, while realizing that must pay back the debt his father had accrued over time. Thus, his romance with Julia is effectively dead, and he never hears about Julia until the news that a betel-nut stand worker has been found killed. This betel-nut stand worker is none other than Julia Huang. For about one hundred pages of the novel, Lin employs Jing-nan as the perfect narrator to welcome a reader with little understanding of Taipei. Jing-nan carefully and meticulously lays out the density of the city, its cultural particularities, and more importantly, its underground and unofficial economies. Toward the ending of this longer than usual preamble to the noir-plotting, he visits Julia’s family as a mode of honoring her memory. They beseech Jing-nan to find out more about the mysterious circumstances of Julia’s death and though reluctant, Jing-nan agrees. On the way out of the house, he is accosted by a stranger who warns him not to investigate. Later on, this stranger reappears and makes the same warning and punctuates his threat with ominous promises of physical harm and death. Thus begins the noir-plot that readers might have been waiting for, but Lin is really balancing more than one narrative here. On one level, the novel is really a character study of Jing-nan, who simultaneously comes to tell us about the complicated historical and social texture of Taiwan, which includes tensions with aboriginal tribes, the continuing standoff with mainland China, as well as the national drive to modernize and to displace older forms of commerce and culture. On the other, Lin introduces the noir plot as a way to get at some of these social issues and to some extent, then, this mystery doesn’t function as seamlessly as other texts that stick more closely to formula structures. My assessment is no means a critique of Lin’s work, which is multifaceted and benefits from the trademark humor that we’ve come to expect in his writings, but rather to elucidate the varied workings of this novel. Though Jing-nan’s fidelity to solving Julia Huang’s murder can stretch the bounds of credulity, the novel succeeds primarily due to Lin’s construction of a flawed but intriguing noir anti-hero, and we can see this novel as the start of another series.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Ghost-Month-Ed-Lin/dp/1616953268/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1410801485&sr=8-1&keywords=ed+lin+ghost+month

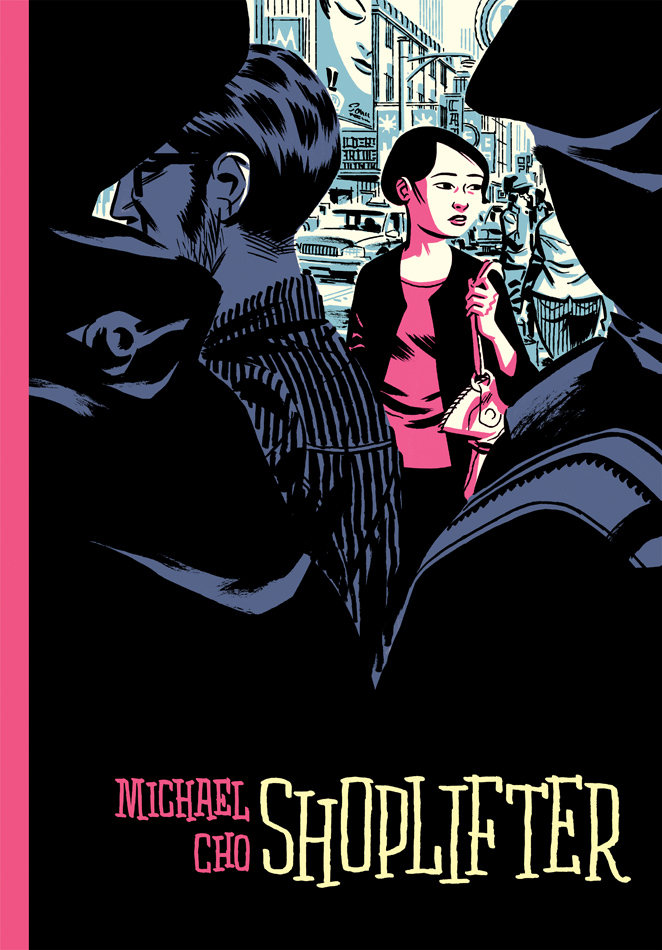

A Review of Michael Cho’s Shoplifting (Pantheon, 2014).

In Shoplifting, Asian Canadian graphic novelist Michael Cho brings us a poignant, nuanced narrative of a young woman trying to figure out her path in life. Our protagonist is Corinna Park, who may or may not be Asian American (an issue I’ll come back to later). She works for an advertisement agency in New York City, but finds her job less than fulfilling. The narrative starts on a day when she’s in a boardroom meeting coming up with an advertising campaign for a perfume that will be marketed to 9 year old girls. She makes an off-color remark that gestures to the sense of ennui that she feels working in a company that is far from her passion. As an undergraduate, Corinna majored in English and thought that she’d one day write novels. Instead, she feels lonely, socially anxious, and generally finds her job desultory. This graphic novel is a coming-of-age that begins when Corinna is brought in by the head of the company and told to rethink why she is at the advertising agency. The title refers to an illicit habit that Corinna maintains whenever she is at the local grocery store. She manages to shoplift a magazine by inserting it in between the pages of a newspaper. She doesn’t provide a reason for why she does it; indeed, she doesn’t lack the money to buy the newspaper but it gives her a kind of thrill. The shoplifting is of course a larger metaphor for the fact that Corinna needs a jumpstart, some sort of obvious sign to move into a new occupation or life trajectory. Fortunately, the graphic novel provides a conflation of different events that lead Corinna to make a monumental decision. Cho’s art has a nice cartoon-style to it. The production design team also saw fit to use a four-toned color scheme system, where pink is mixed in with grays, blacks, and whites.

The use of pink to structure the color is an interesting one and gives the graphic narrative a kind of lighter feel to it than the content of the story would probably allow for on its own. Cho is particularly effective at rendering the alienation that can come with living in a metropolis: Corinna is often framed in scenes with a ton of other individuals, whether commuting by subway or at some sort of gathering. A particular favorite detail of mine was Cho’s focus on internet dating, a quagmire of hilariously bad profiles that Corinna must sift through when she gets home. But, perhaps, the most intriguing element is Cho’s choice to veil Corinna’s ethnic background. With a Korean surname, it would seem very possible that she’s Asian American, but there’s nothing contextually provided that would determine this with any sort of certitude. It brings to mind the question of how race gets represented in the visual register and how graphic novels present more avenues for cultural critics to attend to the complexities of racial formation. A wonderful work, the first I hope of many more by Cho. Certainly, a book I will adopt for future classroom courses on the graphic novel.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Shoplifter-Michael-Cho/dp/030791173X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1409183592&sr=8-1&keywords=michael+cho

With apologies as always for any typographical, grammatical, or factual errors. My intent in these reviews is to illuminate the wide ranging and expansive terrain of Asian Anglophone literatures. Please e-mail ssohnucr@gmail.com with any concerns you may have.

In this post, reviews of: Bilal Tanweer’s The Scatter Here is Too Great (Harper, 2014); Farzana Doctor’s Six Metres of Pavement (Dundurn, 2011); Lily Yuriko Nagai Havey’s Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp (University of Utah Press, 2014); Ed Lin’s Ghost Month (Soho Crime, 2014); Michael Cho’s Shoplifting (Pantheon, 2014).

A Review of Bilal Tanweer’s The Scatter Here is Too Great (Harper, 2014).

Bilal Tanweer’s ambitious and formally inventive debut The Scatter Here is Too Great follows a revolving cast of characters who are linked by one tragic event: a bomb blast in Karachi, Pakistan that leaves many injured and dead. The bomb blast is a red herring, though, and that fact is only made clear in the novel’s final sequence. Indeed, readers might be looking too much into the source of the blast, what caused it, and the motivations for its detonation, without realizing that we’re missing the point. Tanweer’s true protagonist in the city of Karachi, how it has been imagined and remade especially in light of terrorist discourse and the projection of Islamic Fundamentalism on countries in that region. Tanweer’s project, then, is to particularize experience and texturize how the city is interfaced and understood from a variety of different perspectives. Called a “novel in stories,” it follows a number of different characters, shifting narrative perspectives constantly (especially between first and second person). Each section of the novel seems to slightly advance the story, moving us closer and closer physically to the blast. One of the most important connections it seems is the place of the writer in this modernizing city. Indeed, one of the returning figures is a subeditor who is tasked with understanding how to interface with the many facets of Karachi and demystifying its representations. This character muses: “All these stories, I realized, were lost. Nobody was going to know that part of the city as anything but a place where a bomb went off. The bomb was going to become the story of this city. That’s how we lose the city—that’s how our knowledge of what the world is and how it functions is taken away from us—when what we know is blasted into rubble and what is created in its place bears no resemblance to what was and we are left strangers in a place we know, that we ought to have known. Suddenly, it struck me that that’s how my father experienced this city. How, when we walked this city, he was tracing paths from his memory to the present—from what this place had been to what it had become” (165). It would seem that the writer in all of his metafictional conceits is taking himself to task for this very same purpose, trying to create some sort of narrative that links time and place to the urban experience. The form of the novel itself is then part of the key to understanding Tanweer’s rhetoric: not everything will cohere, but the fragmentation is part of the complexity and the beauty of Karachi, a city that we understand is more than a bomb, more than Islamic fundamentalism, more than a site that has been determined to be a terrorist stronghold. I agree with other reviewers that the story can sometimes meander in ways that are distracting to readers, but Tanweer’s prose is so compelling, especially the philosophical renderings that appear in the opening and closing chapters that you’ll be lulled into Karachi’s representationally rich character configurations, including an ambulance driver undone by two figures who seem to represent the end of the world and two young lovers who seek to find a place to be alone in a city with too many eyes.

Buy the book here:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Scatter-Here-Too-Great/dp/0062304410/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=undefined&sr=8-1&keywords=the+scatter+here+is+too+great

A Review of Farzana Doctor’s Six Metres of Pavement (Dundurn, 2011).

The great thing about the archive of “literatures penned by writers of Asian descent in English” (otherwise known as Asian Anglophone) is that the depth of its reach seems unending. There’s always a new writer that I find that I feel like I should have already heard of but haven’t, which brings me to Farzana Doctor, a queer Asian Canadian writer, who has published two novels. I review Six Metres of Pavement here, which is told in the third person perspective and primarily follows two characters: Ismail Boxwala, a Muslim Indo Canadian who is divorced, something that occurs in the wake of a tragic accident. He had left his infant daughter in his car while at work and Zubeida (nicknamed Zubi) dies from sun exposure. His wife, Rehana, attempts to assuage to the situation by suggesting they have another child, but Ismail suffers erectile dysfunction, no doubt related to his anxiety that he cannot possibly father another child, fearing that he may again be negligent. Celia Sousa has just moved into the neighborhood with his daughter Lydia and her son-in-law. Celia is in mourning; her mother and her husband Jose have both passed away recently, and she struggles to find a way out of her daily melancholy. It’s been about eighteen years since Zubi died when the novel opens, and Ismail struggles with a drinking habit. He falls into meaningless sexual dalliances with women at the local bar; he also strikes up a friendship and sexual relationship with a local there named Daphne, who ends up proclaiming her queerness and then joining an AA group. It is Daphne who encourages Ismail to take a creative writing class, and it is there that Ismail makes a strong friendship with a fellow classmate Fatima, even after he questions whether or not to stay enrolled (Daphne quickly drops out of the class leaving Ismail abandoned). It’s quite clear from the get-go that Doctor is setting up a romance plot between Ismail and Celia, and it takes too long to get there, but fortunately Doctor also provides us with an interesting friendship plot that occurs between Fatima and Ismail. Both Fatima and Ismail hail from similar ethnic backgrounds (though Fatima is a generation younger) and when Fatima is thrown out of the house, with no support for her livelihood, education, and other such things, she has to increasingly rely on Ismail’s help just to survive. Fatima, as we soon discover, is a feminist, an anticolonialist, steeped in academic rhetoric concerning social inequality, and most importantly for our understanding: she’s a lesbian. gasp To a certain extent, Doctor’s structure strangely enough replicates a heteronormative family unit, as at one point, it seems possible that Ismail will marry Celia, and that Fatima has become a kind of surrogate daughter (a kind of imperfect replacement for Zubi). Though the novel takes too long to set up the connection between Celia and Ismail—indeed, Doctor is a talented writer and it’s perfectly clear that both characters are traumatized, so we could have used some editing in the first 100 pages—the sociopolitical import of the novel is obvious, and the novel especially provides the kind of ending not usually fit for so many characters who exist on society’s fringes. Somehow, Doctor manages to provide us with a convincing ending where outcasts and pariahs do not necessarily succumb to violent deaths and premature termination from the plotting.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Six-Metres-Pavement-Farzana-Doctor/dp/1554887674/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1408805340&sr=8-1&keywords=six+metres+of+pavement

A Review of Lily Yuriko Nagai Havey’s Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp (University of Utah Press, 2014).

What an absolutely amazing book! There can be no other estimation for such an important document that is part of the long-standing recovery effort related to the Japanese American internment experience. Lily Yuriko Nagai Havey’s Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp is a mixed-genre, creative nonfiction memoir that employs photographs, narrative, and watercolor paintings to represent and to give life to Havey’s experiences as a ten-year old who first must endure living at an assembly center and then in the harsh conditions of Colorado’s Amache internment camp. The narrative is straightforward enough and one that recalls other internment works (such as Yoshiko Uchida’s Desert Exile, Mitsuye Yamada’s Desert Run, etc) in its depiction of the monotony, the psychic struggles, and the everyday desultory life of languishing in what is basically an inhospitable place. There are moments of pleasure and even happiness, which erupt in Havey’s narrative in unexpected places: the light of the sun when it hits a cold and barren landscape or the return of a father from long periods away (working outside of the internment camp in order to escape its confines and to provide for the family). In other moments, we constantly see how the internees make the most of meager circumstances, continuing to persevere despite their imprisonment. Again, it is the minor moments which surface as a brutal and stark reminder of indomitable spirits, such as the desire of Havey’s mother to continue polishing the pot-bellied stove, or the move to decorate the ramshackle interiors of the interment barracks. But, what makes Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp so dynamic and so indispensable is its visual catalog, one that includes photographs (indeed, as Havey notes, in the last year of the internment camp, a camera was able to be used by residents) and watercolor paintings that Havey created over time to represent her experiences. The watercolor paintings are notable in that they are far from directly representational: most have abstract and symbolic qualities that seem exactly appropriate as a kind of formal conceit that illuminates such a fragmenting and harrowing experience.

Here’s a link to one of the watercolor paintings:

http://artistsofutah.org/15Bytes/index.php/lily-havey-reads-gasa-gasa-girl-goes-to-camp/

Havey often uses pastels (an effect to a certain extent of the watercolor approach), which ends up also functioning within a light scheme that comes off as ghostly. As these watercolors accompany the direct narrative of the internment, a multifaceted portrayal emerges that reminds us of the continued work that needs to be done in order to reconsider how this experience impacted so many Americans (Japanese in ethnicity and otherwise). Finally, I would like to remark on the production quality of this book: the pages used are the kinds found in art and painting studies, with a glossy finish. Certain to stand the test of time, one must pick up this essential and new addition to the canon of internment literatures.

Internment literatures based upon place:

Topaz: Yoshiko Uchida’s Desert Exile; Julie Otsuka’s When the Emperor Was Divine

Minidoka: Mitsuye Yamada’s Camp Notes and Other Writings

Manzanar: Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston’s Farewell to Manzanar

Heart Mountain: Lee Ann Roripaugh’s Beyond Heart Mountain

Poston: Cynthia Kadohata’s Weedflower

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Gasa-Girl-Goes-Camp-Behind/dp/1607813432/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1410191557&sr=8-2&keywords=gasa+gasa+girl

A Review of Ed Lin’s Ghost Month (Soho Crime, 2014).

So when I picked up Ed Lin’s Ghost Month, I automatically assumed it was another book in Lin’s Robert Chow’s detective series (which includes This is a Bust, One Red Bastard, and Snakes Can’t Run). Instead, we have another book entirely, which revolves around Jing-nan (aka Johnny), a twenty-ish character languishing in a life he never wanted (inheriting the debts of his father and running a stall out of Taipei’s famed Night Market) living in a country he doesn’t want (Taiwan). The opening of the novel begins inauspiciously enough with Jing-nan discovering that the love of his life Julia Huang has been murdered. Jing-nan hadn’t kept in touch with Julia because of a promise he made that he would only marry her if he had established himself in a career and with full preparedness for life as a married couple. When he must leave UCLA without finishing his degree and returns to Taiwan, but not soon after, his mother dies in a tragic accident and his father dies just three weeks later due to health issues. Needless to say, Jing-nan’s life is turned upside down. He takes on the family business, while realizing that must pay back the debt his father had accrued over time. Thus, his romance with Julia is effectively dead, and he never hears about Julia until the news that a betel-nut stand worker has been found killed. This betel-nut stand worker is none other than Julia Huang. For about one hundred pages of the novel, Lin employs Jing-nan as the perfect narrator to welcome a reader with little understanding of Taipei. Jing-nan carefully and meticulously lays out the density of the city, its cultural particularities, and more importantly, its underground and unofficial economies. Toward the ending of this longer than usual preamble to the noir-plotting, he visits Julia’s family as a mode of honoring her memory. They beseech Jing-nan to find out more about the mysterious circumstances of Julia’s death and though reluctant, Jing-nan agrees. On the way out of the house, he is accosted by a stranger who warns him not to investigate. Later on, this stranger reappears and makes the same warning and punctuates his threat with ominous promises of physical harm and death. Thus begins the noir-plot that readers might have been waiting for, but Lin is really balancing more than one narrative here. On one level, the novel is really a character study of Jing-nan, who simultaneously comes to tell us about the complicated historical and social texture of Taiwan, which includes tensions with aboriginal tribes, the continuing standoff with mainland China, as well as the national drive to modernize and to displace older forms of commerce and culture. On the other, Lin introduces the noir plot as a way to get at some of these social issues and to some extent, then, this mystery doesn’t function as seamlessly as other texts that stick more closely to formula structures. My assessment is no means a critique of Lin’s work, which is multifaceted and benefits from the trademark humor that we’ve come to expect in his writings, but rather to elucidate the varied workings of this novel. Though Jing-nan’s fidelity to solving Julia Huang’s murder can stretch the bounds of credulity, the novel succeeds primarily due to Lin’s construction of a flawed but intriguing noir anti-hero, and we can see this novel as the start of another series.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Ghost-Month-Ed-Lin/dp/1616953268/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1410801485&sr=8-1&keywords=ed+lin+ghost+month

A Review of Michael Cho’s Shoplifting (Pantheon, 2014).

In Shoplifting, Asian Canadian graphic novelist Michael Cho brings us a poignant, nuanced narrative of a young woman trying to figure out her path in life. Our protagonist is Corinna Park, who may or may not be Asian American (an issue I’ll come back to later). She works for an advertisement agency in New York City, but finds her job less than fulfilling. The narrative starts on a day when she’s in a boardroom meeting coming up with an advertising campaign for a perfume that will be marketed to 9 year old girls. She makes an off-color remark that gestures to the sense of ennui that she feels working in a company that is far from her passion. As an undergraduate, Corinna majored in English and thought that she’d one day write novels. Instead, she feels lonely, socially anxious, and generally finds her job desultory. This graphic novel is a coming-of-age that begins when Corinna is brought in by the head of the company and told to rethink why she is at the advertising agency. The title refers to an illicit habit that Corinna maintains whenever she is at the local grocery store. She manages to shoplift a magazine by inserting it in between the pages of a newspaper. She doesn’t provide a reason for why she does it; indeed, she doesn’t lack the money to buy the newspaper but it gives her a kind of thrill. The shoplifting is of course a larger metaphor for the fact that Corinna needs a jumpstart, some sort of obvious sign to move into a new occupation or life trajectory. Fortunately, the graphic novel provides a conflation of different events that lead Corinna to make a monumental decision. Cho’s art has a nice cartoon-style to it. The production design team also saw fit to use a four-toned color scheme system, where pink is mixed in with grays, blacks, and whites.

The use of pink to structure the color is an interesting one and gives the graphic narrative a kind of lighter feel to it than the content of the story would probably allow for on its own. Cho is particularly effective at rendering the alienation that can come with living in a metropolis: Corinna is often framed in scenes with a ton of other individuals, whether commuting by subway or at some sort of gathering. A particular favorite detail of mine was Cho’s focus on internet dating, a quagmire of hilariously bad profiles that Corinna must sift through when she gets home. But, perhaps, the most intriguing element is Cho’s choice to veil Corinna’s ethnic background. With a Korean surname, it would seem very possible that she’s Asian American, but there’s nothing contextually provided that would determine this with any sort of certitude. It brings to mind the question of how race gets represented in the visual register and how graphic novels present more avenues for cultural critics to attend to the complexities of racial formation. A wonderful work, the first I hope of many more by Cho. Certainly, a book I will adopt for future classroom courses on the graphic novel.

Buy the Book Here:

http://www.amazon.com/Shoplifter-Michael-Cho/dp/030791173X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1409183592&sr=8-1&keywords=michael+cho